This essay appeared in The Washington Post Friday, from a Catholic father expressing the anxieties a lot of parents have these days about children simply being around priests, particularly as altar servers:

I am as conflicted as many other Catholics. The church has been a strong fiber threading through the various stages of my life, shepherding me through the most difficult times. A late priest who was a longtime family friend of my in-laws used to say Mass at their Bethany Beach house on summer Sunday afternoons, the kitchen island serving as the altar for a sunburned congregation of a half-dozen. That same priest married my wife and me. Seven years later, a different priest sat in our living room and counseled us during a difficult pregnancy. It was he who made an emergency visit to the hospital one morning a couple of months later to baptize our baby, who died hours later.Maybe that’s why, despite the wretched stain that pedophile priests have left on their religion, and the trauma they have inflicted on thousands, I firmly believe that the good priests far outnumber the bad ones, and I believe that through the good ones, God’s will is done on earth. Is that naivete? Hope? Faith?Faith, we are taught, is the belief in that which we cannot see. You have seen and believed, the risen Jesus told a doubting Thomas, but blessed are they who have not seen and yet still believe.I believe — I must believe — that the priests I am allowing to interact with my children are honest, pious men.…This Sunday, my children will once again enter the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in northern Baltimore, they will dip their hand in holy water, make the sign of the cross and offer their service to the church.My wife and I will sit in the pew and hope and pray that today, tomorrow, always, the church will remain a safe place for them. It is a huge act of faith.

We hear this from time to time. “My child wants to be an altar server — is that safe? Am I crazy to let him do it? Will they have to get undressed in front of priests to put on their vestments?!” (If you’re wondering: no. Kids are fully clothed at all times. Albs or cassocks go over their street clothes.)

These fears are understandable. But a few points should be made.

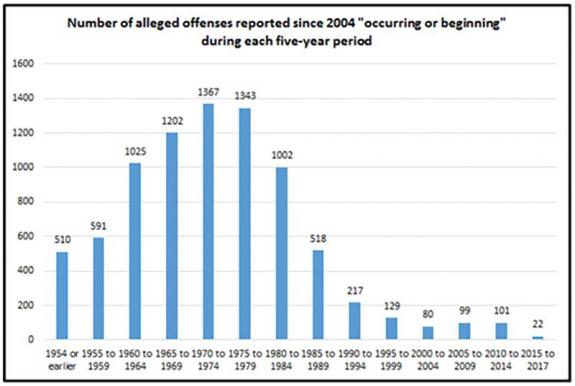

First, most cases are old. Very old. Given what we hear in the media, parents can’t be faulted for thinking predators are lurking in the shadows of every Catholic parish, even as I write this. That ain’t necessarily so. Most of the allegations surfacing over the last several months date back decades, and many of the accused are now dead. The accusations date to a time long before protective measures were put in place to identify, investigate and punish priests accused of abuse. (And they fit a pattern: nearly half of the accused in the Pennsylvania Grand Jury report are dead; a few were born in the 19th century. And as the John Jay report noted: “The majority of men in this study were born between 1920 and 1950 and were ordained in their mid- to late-twenties.” The most common decade of birth for alleged abusers was the 1930s and the most common decade of ordination was the 1960s.

As for more recent incidents, the latest USCCB audit notes:

In 2017, over 2.5 million background checks were conducted on Church clerics, employees, and volunteers. Over 2.5 million adults and 4.1 million children have also been trained on how to identify the warning signs of abuse and how to report those signs.Twenty-four new allegations came from minors. As of June 30, 2017, six were substantiated and the clergy were removed from ministry. These allegations came from three different dioceses. Four of the six allegations were against the same priest. Eight allegations were unsubstantiated as of June 30, 2017. Three were categorized as “unable to be proven” and investigations were still in process for five of the allegations as of June 30, 2017.

America magazine reported last year:

In the last three years, 22 allegations of abuse occurring during 2015-2017 have been made. This is an average of about seven per year nationwide in the church. That is far too many. Nothing is acceptable other than zero. At the same time, to put those reports in some context, 42 teachers in the state of Pennsylvania, where the grand jury reported from, lost their licenses to educate for sexual misconduct in 2017. As recently as 2015, 65 teachers in the Los Angeles Unified School District (L.A.U.S.D.) were in “teacher jail” for accusations of sexual abuse or harassment in that county alone. The current wave of educator sexual misconduct has yet to receive the same aggregation and attention that clergy sexual abuse has by the media (although The Washington Post has rung a warning bell and Carol Shakeshaft has written extensively on it in academic work). As the John Jay researchers note, “No other institution has undertaken a public study of sexual abuse and, as a result, there are no comparable data to those collected and reported by the Catholic Church.” (More on this below.)

Secondly, it’s not just a Catholic thing. The horrifying reality is that this scourge iseverywhere:

A 2018 study by three criminologists revealed that hundreds of claims of sexual abuse are made every year against pastors and other Protestant church leaders (despite the fact that most Protestant pastors are married). According to the study’s authors:Three faith-based insurance companies that provide coverage for 165,500 churches—mostly Protestant Christian churches and 5500 other religious-oriented organizations—reported 7,095 claims of alleged sexual abuse by clergy, church staff, congregation members, or volunteers between 1987 and 2007. This is an average of 260 claims of alleged sexual abuse per year, which resulted in $87.8 million in total claims being paid.

Ernie Allen, the director of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, said in an interview with Newsweek magazine, “We don’t see the Catholic Church as a hotbed of this or a place that has a bigger problem than anyone else. I can tell you without hesitation that we have seen cases in many religious settings, from traveling evangelists to mainstream ministers to rabbis and others.”

Third— as noted above — it’s not just a religious thing, either :

A 2004 report from the U.S. Department of Education indicated that one out of ten public school students experience some kind of unwanted sexual advance from an educator. Two-thirds of those students say the advance involved some kind of physical contact. According to the report’s author, “more than 4.5 million students are subject to sexual misconduct by an employee of a school sometime between kindergarten and twelfth grade.”Why, then, does the public still associate priests with sexual abuse and not public school teachers, who may be in the present moment more likely to abuse children?Perhaps it’s because news media tend to report on crimes like clergy abuse in “waves” that can leave an impression in the public mind that they’re more common than they really are. (For example, pervasive media coverage of mass shootings may lead people to think violent crime is at an all-time high, but according to FBI statistics violent crime actually dropped by forty-eight percent between 1993 and 2016.) Also, since one-third of those who were abused between 1960 and 1980 waited to report the crime until after 2002, and since fresh reports of investigations, like that of the Pennsylvania grand jury this year, are treated as news even though the incidents they cover are usually decades old, there can be a compression of events that magnifies their perceived frequency.

Fourth, the Catholic clerical culture is changing. I can tell you it is rare these days to find a priest or deacon who will spend any time alone with a minor — and many won’t even meet alone with an adult. The risk of a false accusation is just too great. (Whenever I meet with someone, whether an adult or a minor, I make sure the door is open and, if possible, someone else is within earshot, if not also in the room.) Also, every adult working with children is required to undergo training to detect problems or warning signs of abuse, and to report them immediately. For these and other reasons, the likelihood of abuse happening has diminished significantly.

Finally, whether you realize it or not, the Catholic Church may be the safest place for children. The Church is doing more than almost any other institution to battle this nightmare. And, despite all its problems and flaws, it’s working.

As David Gibson wrote a few years back:

Whatever its past record, the Catholic Church in the U.S. has made unparalleled strides in educating their flock about child sexual abuse and ensuring that children are safe in Catholic environments.Over the past 10 years, Catholic parishes have trained more than 2.1 million clergy, employees, and volunteers about how to create safe environments and prevent child sexual abuse. More than 5.2 million children have also been taught to protect themselves, and churches have run criminal background checks on more than 2 million volunteers, employees, educators, clerics and seminarians.Allegations of new abuse cases continue to decline, as they have since 1980, and appear to reflect the effectiveness of some of the charter’s policies as well as ongoing efforts to increase screening of seminarians and to deal with suspected abusers before they claim multiple victims.

The analysis by America magazine has some excellent detail about all this, including information about when abuse occurred and when it was reported — and why.

None of this is meant to forgive or justify or explain away the horror of sex abuse. This remains a pervasive evil that we as a culture and as a society need to battle, using every weapon available. The toll it has exacted on generations of innocent lives is devastating — and attention must be paid. Justice must be served.

But any parent wondering about how safe their child might be among Catholic clergy in 2019 should know the facts.