This post originally appeared on Aug. 28 on 1964, a research blog published by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate. It has since been updated with new information, as noted below.

As a survey researcher who has studied Catholic reactions to news of allegations of clergy sexual abuse of minors since 2002, I have noticed that there is a detail about the crisis that seems to get distorted at times. In 2012, the last time we asked Catholics about the crisis in a national poll, 21 percent of adult Catholics could correctly identify that the abuse cases were more common before 1985 than since. The fact that any abuse occurred at all, regardless of when, is horrifying to me, and the victims deserve justice and anything that could help them with the damages that resulted from these criminal acts. Yet this detail is important in understanding the causes of the scandal, what legal actions are possible and the steps that can be taken to prevent any future abuse.

Only 21 percent of adult Catholics could correctly identify that the abuse cases were more common before 1985 than since.

Tweet this

The authors of the Pennsylvania grand jury report were careful to note, “We know that the bulk of the discussion in this report concerns events that occurred before the early 2000’s” (see Page 6). At the same time they correctly note that abuse “has not yet disappeared” and there are a couple of more recent allegations detailed in their findings.

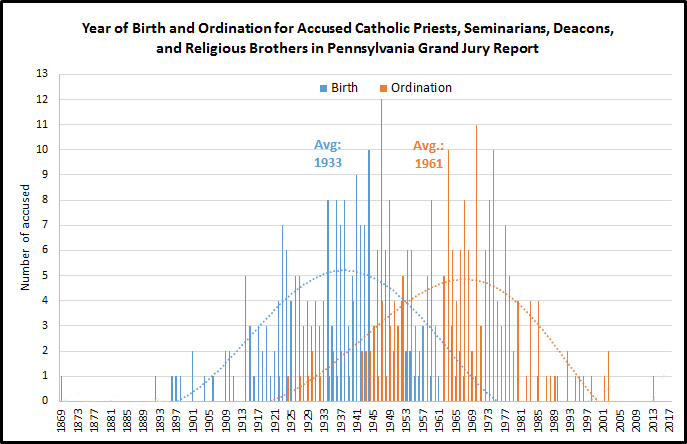

As they note, “Many of the priests who we profile here are dead” (Page 12). Dates for birth, year of ordination and death are not available for all the accused in the report (some are seminarians or brothers and were never ordained). But 44 percent of the accused in the report are known to be dead (five were born in the 19th century). Their average age at death was 73. Among the accused who are still alive or presumed alive, the average age today is 71. Priests accused of abuse in the Pennsylvania grand jury report, on average, were born in 1933 and ordained as priests in 1961. Outside of Pennsylvania, allegations of abuse have also been levied recently against former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick. He was similarly born in 1930 and ordained a priest in 1958.

There is something to this generational pattern, and this finding was first uncovered in the scientific study of the abuse crisis in 2004 by researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. They noted in 2004, “The majority of men in this study were born between 1920 and 1950 and were ordained in their mid- to late-twenties.” The most common decade of birth for alleged abusers was the 1930s and the most common decade of ordination was the 1960s. This profile has not changed in allegations that emerged in the 14 years that have followed—including the recent grand jury report. No new wave of abuse has emerged in the United States.

The same scandal with new details

The clergy sex abuse scandal unfolding in the news today is the same public scandal that erupted with national media reports in 2002 (beginning in Boston). It is likely, but no one can be sure, that the cases in the grand jury report have already been present in existing allegation totals (reports to the John Jay researchers are cited as a source for information about allegations in the grand jury report). Just as then, the abuse in the headlines most often occurred in the 1960s through the 1980s.

What is new in the Pennsylvania grand jury report is a level of detail that previous investigations have not often included. The authors report on a “playbook” that church leaders allegedly used to handle allegations of clergy sex abuse in the state prior to 2002. “It seemed as if there was a script. Through the end of the 20th century, the dioceses developed consistent strategies for hiding child sex abuse” (Page 297). This strategy included the use of euphemisms in documentation that minimized abuse as conduct that was “inappropriate” or related to “boundary issues.” The dioceses’ investigations appeared to be deficient or biased, according to the grand jury. Many accused priests were sent for treatment in a clinical approach to the abuse rather than what should have occurred—criminal reporting. Once these treatments were considered complete, abusers were often returned to ministry in new assignments. The allegations were rarely, if ever, disclosed publicly. Victims rarely received the care they needed, let alone justice. The grand jury concludes, “The repeating pattern of the bishops’ behavior left us with no doubt that, even decades ago, the church understood that the problem was prevalent” (Page 300). Further, “The bishops weren’t just aware of what was going on; they were immersed in it. And they went to great lengths to keep it secret. The secrecy helped spread the disease” (Page 300).

“It seemed as if there was a script. Through the end of the 20th century, the dioceses developed consistent strategies for hiding child sex abuse.”

Tweet this

This strategy is not entirely dissimilar to the responses of other institutions when faced with any accusations of sexual abuse of minors, whether it has been scouting groups, public schools, prep schools, universities or youth athletics. These types of institutions seem to attract sexual abusers of minors who seek positions of trust and respect with access to young people. The John Jay researchers noted in 2011: “Sexual victimization of children is a serious and pervasive issue in society. It is present in families, and it is not uncommon in institutions where adults form mentoring and nurturing relationships with adolescents, including schools and religious, sports, and social organizations” (Page 5).

The church failed in responding to accusations of abuse and more often chose to cover up the criminal activity than disclose and report it. The church in some cases sought nondisclosure agreements in civil settlements with victims—a practice that the grand jury believes should be abolished. What was often different in the church than elsewhere, especially prior to 2000, was the clinical response to abuse—sending abusers for treatment and allowing them to return to ministry after this was completed. These were grave errors in judgment. This allowed abusers the potential to return to work and continue to abuse. It also ignored the legal obligation to seek justice for crimes committed.

That playbook, to the degree it was used broadly, appears to have changed in 2002. The grand jury report’s authors note, “On the whole, the 2002 [Dallas] Charter did move things in the right direction” and that “external forces have also generated much of the change” (Page 302). They note with concern that the church’s 2002 Dallas Charter—officially called The Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People—still leaves too much of the decision making to diocesan bishops. But the external changes brought by mandated abuse reporter laws, longer statutes of limitations and increased public awareness have created a new reality. They write, “Today we sense some progress is made” (p. 303), often by actors external to the church rather than from within it.

New allegations of abuse

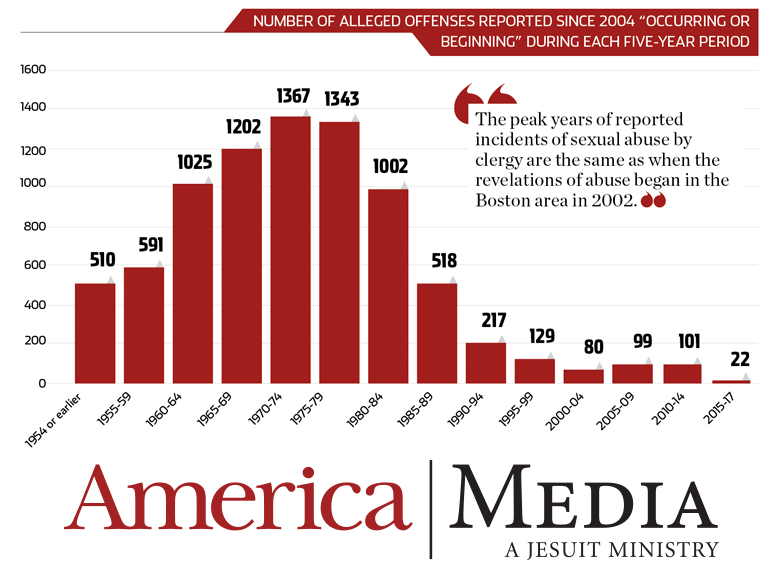

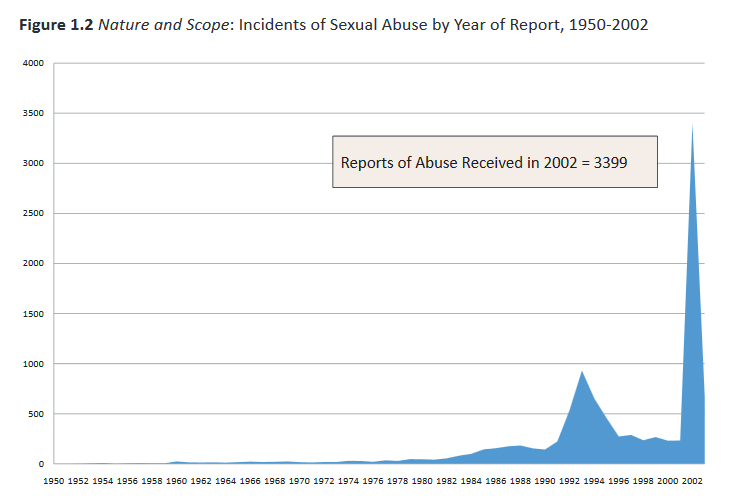

Have new allegations of abuse declined as a result? The John Jay researchers aggregated the number of allegations of clergy sexual abuse of minors from 1950 to 2002. Their study included allegations made by 10,667 individuals. CARA has collected the numbers of new allegations of sexual abuse by clergy since 2004. CARA’s studies, through 2017, include 8,694 allegations. The distribution of cases reported to CARA are nearly identical to the distribution of cases, over time, in John Jay’s results. We know the year that each alleged abuse began for 8,206 cases. For 488, this is not known. The chart below left shows the cases where we can place these in time.

New abuse allegations have not disappeared. In the last three years, 22 allegations of abuse occurring during 2015-2017 have been made. This is an average of about seven per year nationwide in the church. That is far too many. Nothing is acceptable other than zero. At the same time, to put those reports in some context, 42 teachers in the state of Pennsylvania, where the grand jury reported from, lost their licenses to educate for sexual misconduct in 2017. As recently as 2015, 65 teachers in the Los Angeles Unified School District (L.A.U.S.D.) were in “teacher jail” for accusations of sexual abuse or harassment in that county alone. The current wave of educator sexual misconduct has yet to receive the same aggregation and attention that clergy sexual abuse has by the media (although The Washington Post has rung a warning bell and Carol Shakeshaft has written extensively on it in academic work). As the John Jay researchers note, “No other institution has undertaken a public study of sexual abuse and, as a result, there are no comparable data to those collected and reported by the Catholic Church” (Page 5).

The current wave of educator sexual misconduct has yet to receive the same aggregation and attention that clergy sexual abuse has by the media.

Tweet this

“It is happening in other institutions” is by no means any sort of excuse and that is not what is intended by referring to these realities. Instead, these other cases provide a context, which becomes important when someone who reads news of abuse occurring decades ago in churches in Pennsylvania decides to attack a priest today in Indiana or when a parent feels their children will be less safe in a Catholic school than a public school. It also points to the dangers of thinking that incidents of sexual abuse are unique to Catholic institutions.

As the grand jury report authors note, the church has changed in the last 15 years. But you cannot “fix” the past nor can it be erased. This won’t all fade away. It’s nothing that can ever be outrun. You have to deal with it. The church did not sufficiently do so in 2002 and the years that followed. Creating new policies to prevent future abuse are not a sufficient response to the legacy of what happened. Now, in 2018, it is time to lift the veil of any secrecy that remains. If not, the same cases will emerge again and again as if these were a wound that scabs but never heals. Every time that scab is removed it will bleed again and again. As painful as it is now, it is the time to deal with this great injury the church brought upon itself. If anything, the re-emergence of these cases again and again should reveal that this wound has potentially deadly consequences if it is not dealt with completely once and for all.

Update (Aug. 29): Some reactions to this post have asked about the impact of known delays in reporting by victims. There has been no substantial shifting forward in time of the alleged abuse trend between 2002 and 2017. The accusations continue to fit the historical pattern. We would expect the trend to move forward in the last 15 years if reporting delays were evident, but this has not been the case. No new wave of allegations similar to the past has occurred to date. It is also likely that most, if not all, the Pennsylvania cases are already in existing reported accusation totals.

Update (Aug. 30): We continue to hear feedback about the delays in reporting related to the age of the victim. The data regarding accusations in the Catholic Church specifically appear to be much more event-driven than age-driven. Rather than victims reaching a certain age and coming forward, it has more often been the case that abuse being in the news has led victims to come forward in large numbers. The chart at left is from the John Jay research (Page 9) and shows when allegations were reported up to 2002. One can see the spike in the 1990s, after a series of cases in the news and again in a larger magnitude in 2002 in the wake of news of abuse cases in Boston. Since 2004, new allegations have averaged 618 per year (438 in 2017). Regardless of when reports are made, the accusations often fit the existing pattern described above for when the abuse occurred. Four allegations of abuse occurring in 2017 were made in 2017.